Introduction

The old American Dream … was the dream of the Puritans, of Benjamin Franklin’s “Poor Richard”… of men and women content to accumulate their modest fortunes a little at a time, year by year by year. The new dream was the dream of instant wealth, won in a twinkling by audacity and good luck. [This] golden dream … became a prominent part of the American psyche only after Sutter’s Mill.

— H. W. Brands, The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream

In 1848, the discovery of gold in California spread across the United States and around the world. It turned the nation into a frenzy of hope and excitement. Consequently, hundreds of thousands of men embarked on a journey to seek fortune from the uncovered land, leaving their families behind. Among the miners were mostly the impoverished, who desperately sought wealth by sieving gold with their callused hands and ragged clothes. Despite hardship, the belief in gaining massive wealth through hard work and luck encouraged the continuous flow of migrants to California. This notion of the “California Dream,” however, did not last long as they soon realized that only a few of them had the luck to ‘strike gold.’

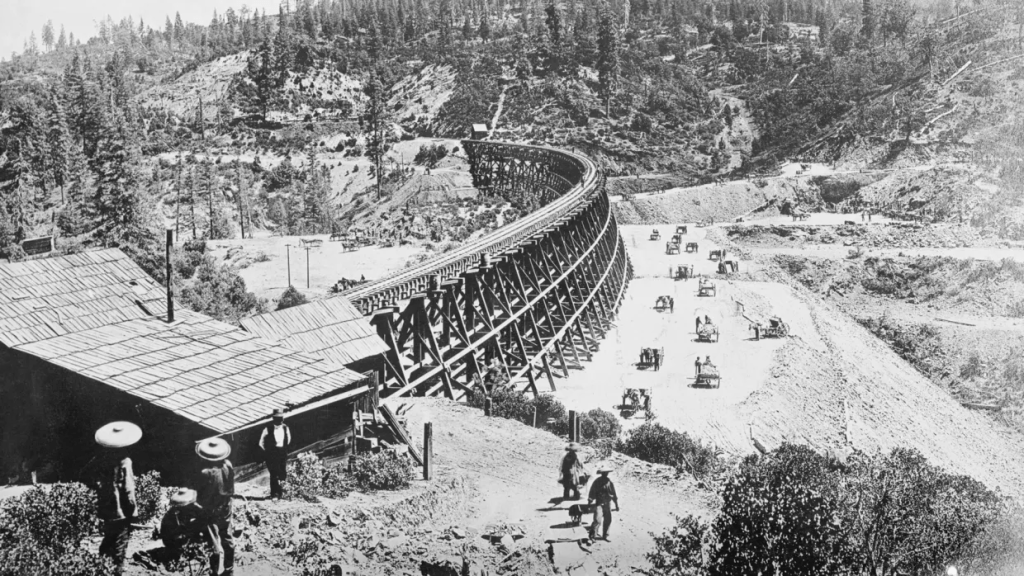

By 1865, as the prosperity promised by gold mining began to tarnish, railroads started to offer another shining vision of possibility. In the wake of the invention and subsequent widespread prevalence of locomotives in the 1830s, the early development of the railroad industry was initially confined to the East Coast. In 1857, the famous engineer Theodore Judah proposed a plan to construct railroads to the Pacific in “A Practical Plan for Building the Pacific Railroad,” specifically through the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Eventually, the railroad constructed based on this proposal was named the First Transcontinental Railroad.

The Transcontinental Railroad conjured images of huge steam engines traversing the Mississippi River to the Great Plains, and finally, over the Rocky Mountains. The fact that it was a paramount technological achievement sparked optimism about the future, and of course, the American Dream. Nevertheless, in the pursuit of their American Dream, one group was often neglected: the Chinese workers of the Transcontinental Railroad. During the years of construction, they became the majority workforce of the Central Pacific Company and were known for their efficiency. However, as they were discriminated against and treated poorly, the extreme inequality and harsh living conditions prompted them to initiate a strike in 1867 in the Sierra Mountains. The strike, nonetheless, did not change the fate of the workers as the plea for better wages and living conditions fell on deaf ears.

The Railway Strike of 1867 demonstrated how the American Dream changed over time in ways different groups were affected by the ‘great experiment.’ For example, Chinese workers experienced racial discrimination in terms of working conditions and wages but proved themselves to be obedient but not docile through the strike. The capitalist railroad owners, also known as the “Big Four,” received a positive reputation from the construction of the railroad despite the workers’ low wages and subpar working and living conditions. Many citizens of California had xenophobic views due to jobs being taken by the Chinese, thus prompting the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, making it increasingly challenging for the Chinese to survive in the United States. Over one and a half centuries later, their tragic stories had been scarcely known until their descendants finally came together in 2019 to uncover this hidden history and tell the unrealized American Dream of these Chinese workers from the 19th century.

From Guangdong to ‘Gold Mountain’

The government planned to secure the integrity of the United States with the Transcontinental Railroad. On July 1, 1862, the second year of the Civil War, President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act, which was: “an act to aid in the construction of a railroad and telegraph line from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean, and to secure to the Government the use of the same for postal, military, and other purposes.” This act aimed to tie the separated nation together with the Transcontinental Railroad. While the railroad intended to fuse the divided nation, its cost was the division between ethnic groups, especially discrimination against Chinese and Native Americans.

The drama began when gold was first discovered in California in 1848. A Chinese immigrant living in California presented the thrilling prospect to his hometown Guangdong through a telegram, depicting an endless opportunity to become wealthy in the United States. Since then, San Francisco has forever been named “Gold Mountain” in Chinese. The news soon spread swiftly in Guangdong, as those who had limited concepts of America were intrigued by the gold rush. Despite the negative rumors about America, such as ugly crafty foreigners who kidnapped Chinese children, their ambition overshadowed fear, as they began dreaming about wealth and status after migrating to the United States. To the Chinese, they had the same American Dream as every other white fortune seeker: to secure wealth.

The Guangdong peasants were impoverished and sought a way out. In the 1800s, the Qing dynasty gradually declined and was suppressed by Western nations. As China mostly recognized European goods as inferior, the Qing dynasty gradually halted trade with European countries. After 1684, China closed down multiple trading posts, eventually leaving only Guangdong as the only legitimate trading post in the whole nation. However, China’s loss in the Opium Wars in the mid-1800s forced China to import opium and other goods from Europe, especially Great Britain. Meanwhile, China’s defeat resulted in multiple unfair treaties, forcing the Qing government to impose taxes on peasants.

The destitute peasants could not withstand such an extra economic burden, thus triggering the Taiping Rebellion in 1850. Led by Hong Xiuquan, a Christian who believed himself as the son of God, tens of thousands of peasants started a revolution for religious freedom and economic support. While the rebellion was fought for the peasants, they ironically suffered the most, resulting in 20 to 70 million deaths. The survivors were not better off than the victims, who starved for not being able to afford taxes and lost ownership of lands. The political tensions both within and outside of the nation, and economic difficulties motivated the peasants to look for another way out.

The peasants identified immigration to America as an opportunity to escape from poverty and oppression. As ports in Hong Kong advertised their trips to the United States, they largely attracted a lot of the poor Chinese, who aspired to achieve their American Dream of gaining wealth. Linda Perrin’s depiction of various Hong Kong advertisements contributed to keeping their dreams alive:

Americans are very rich people. They want the Chinaman to come and will make him very welcome. There you will have great pay, large houses, and food and clothing of the finest description. You can write to your friends and send them money at any time, and we will be responsible for the safe delivery …. There are a great many Chinamen there now, and it will not be a strange country. Chinagod is there, and the agents of this house. Never fear and you will be lucky. Come to Hong Kong, or to the sign of this house in Canton, and we will instruct you. Money is in great plenty and to spare in America.

This marked the beginning of hundreds of thousands of Chinese migrating to the United States. No one at the time would have imagined that their future would be so dramatic. To the emigrating Chinese, they were merely leaving their hopeless hometown in search of a better fortune.

The Arrival of Chinese Workers in California

The initial arrival of the Chinese was welcomed. They were well-received because they were viewed as being distinct from the rest of the white people. Multiple local newspapers reported on Chinese arrivals as a positive supplement to the nation. In May 1852, the Daily Alta California, a famous local newspaper, expressed hospitality towards the Chinese: “Scarcely a ship arrives that does not bring an increase to this worthy integer of our population. The China boys will yet vote at the polls, study at the same schools, and bow at the same altar of our own countrymen.” Specifically, the newspaper argued that the recent arrival of the “Chinese boys” brought new liveliness to the West, and they were therefore accepted.

In 1850, out of the 58,000 gold miners in California, only 500 were Chinese. However, from 1852 to the early 1860s, 6,000 to 8,000 Chinese entered San Francisco. While half of them returned to Guangdong years later, others settled down in the United States permanently. The initial warm welcome that white locals showed towards the Chinese, however, would starkly contrast with the complete inhospitality years later.

Meanwhile, the gradually increasing number of Chinese immigrants soon became a vital and noticeable part of the population. In April 1854, the Daily California Chronicle reported the arrival of eight hundred Chinese miners, recognizing their noteworthy existence in California. The newspaper argued the workers “were rising from extreme penury to comparative wealth.” The essence of the newspaper’s argument was that despite its description of the Chinese as subordinate and subservient in all aspects from working capabilities, to stature, and intelligence compared to the Caucasian race, the increase of the population and interracial cooperation prompted temporary economic stability within the region. Since the absence of “black slaves” and “fast dying out” Native Americans, the Chinese took the role of aide to the white men, who were “naturally of the dominant race; they [were] all fitted to be masters.” The Chinese “[were] such a people” welcomed to provide infrastructure and agricultural support to the local development. Eventually, they proved that they contributed more than this.

A plethora of Chinese miners soon gained wealth from the Gold Rush. The Chinese workers were characterized by diligence, teamwork, and the use of technology. The author, Mark Twain, revered the Chinese. “They are quiet, peaceable, tractable, free from drunkenness, and they are as industrious as the day is long. A disorderly Chinaman is rare, and a lazy one does not exist,” Twain wrote in Roughing It.

Mark Twain’s commendation of the Chinese proved their ingenuity and hard work. The destitute living conditions and starvation back in Guangdong already equipped the Chinese with rare capabilities to survive in extreme situations. In California, mining tools, long poles, a wheelbarrow, and some rice were enough for a Chinese laborer to keep an eye on gold. In Northern California, some Chinese miners collaborated to construct a dam separating the Yuba River, aiming to exploit a lucrative gold deposit to its fullest extent. In Utah, others made it possible to mine in the desert by building an irrigation channel from the Carson River to Gold Canyon. Furthermore, the Chinese brought the water wheel, which was an agricultural technology for pumping water, to wash pebbles from gold. Through their everyday effort, they generated enough wealth to stay in America.

Due to the large success of the Chinese in California, envy toward foreign miners arose in California. The prevailing belief that gold in America should be mined by Americans only soon promoted taxes against foreign miners. California passed the Foreign Miners’ Tax Act in 1850, which imposed 20 dollars a month for foreign workers. While this act was rescinded in 1851, it was replaced by the Foreign Miners’ Tax Act in 1852, which taxed an additional four dollars a month on foreigners. Both acts failed to bring wealth into the treasury as planned, instead forcing the population of miners to decrease. Eventually, San Francisco was filled with jobless foreigners, proportional to the impoverished Chinese moving into cities. Besides, these two acts were pioneering because they foreshadowed subsequent restrictions on the Chinese at the governmental level.

The Chinese were explicitly discriminated against at the executive level. If the Foreign Miners’ Tax Acts were merely proving discrimination against all foreigners, the People v. Hall case marked the governmental prejudice towards Chinese exclusively for barring them from testifying against the whites. In 1854, George Hall, a white man, was convicted of murdering Ling Sing, a Chinese man. The original verdict of Hall was guilty and to be hanged as three Chinese and one Caucasian testified. During Hall’s appeal, his lawyer argued that the Chinese were barred from testimonies according to Section 14 of the Act concerning Crime and Punishment, which stated: “No black or mulatto person, or Indian, shall be allowed to give evidence in favor of, or against a white man.”

The Supreme Court then reversed the verdict for People v. Hall. Chief Justice Hugh Murray recognized the Chinese as Indians because Columbus reached the wrong conclusion that San Salvador was a part of China: “From that time, down to a very recent period, the American Indians and the Mongolian, or Asiatic, were regarded as the same type of the human species.” After People v. Hall was overturned, the white miners realized no law would punish them for terrorizing the Chinese. The discrimination against the Chinese was then brought to the railroad.

Working for the Central Pacific Railroad

Governmental discrimination attempted to rectify the codified inequality between the Chinese people and Caucasian Americans. A short anecdote provided by Moon Lee, whose father and grandfather both worked for the Central Pacific, related his forebears’ hardship with the whites. A mild-tempered and hardworking Chinese cook for white railroad workers frequently became the center of pranks. The white workers “sneak[ed] into his tent and t[ied] knots in his pants legs and shirt sleeves. The cook did not make any fuss but just rose earlier and patiently untied the knots and got on with the food preparation.” This story was told repeatedly among the Chinese workers, which emphasized the obedience and submissiveness of the Chinese consistent with the stereotypes.

Luckily, this incident had an interesting turn. “One day, after a particularly savory dinner, the ringleader, ashamed of the tricks, gathered his gang around him and informed the Chinese that hereafter he was their friend and no one would harm him. The Chinese cook’s eyes brightened.” The cook surprisingly presented his humorous side upon hearing this delightful news: “All-li my flens [sic], now I no pee in the soup!” While the Chinese cook’s story had a positive ending, most others did not. A surprising twist like this scarcely occurred in most camps, as the Chinese were generally mocked and looked down upon.

In addition to discrimination, the Chinese workers faced multiple difficulties and dangers. Starting from Sacramento, they needed to prepare for the treacherous work of tunnel digging on the Sierra Nevada. In the spring of 1864, Chinese workers encountered the steep terrain of Boomer Cut in Auburn, California. They blasted the land to provide the foundation for track laying. The work was laborious as workers used black powder and shovels to dig through gravel. The 800-foot-long “cut” was eventually finished in March 1865, with many more “cuts” yet to be constructed.

Despite hardship, the determination of Chinese workers persisted through even more perilous tasks near Mount Sierra. The Chinese were known for their resilience in managing to build the Great Wall, an extraordinary architectural feat completed two centuries ago. They carried similar traits in the construction of American railroads. In the middle of 1865, workers completed the construction in Cape Horn, which was a three-mile road along a steep precipice. The work included clearing obstructions such as rocks and trees and laying tracks along the 45- to 75-degree slope. After Cape Horn, the constructions were increasingly perilous as they approached Mount Sierra.

Then, the Chinese workers conquered the Sierra Nevada. In the fall of 1865, they constructed a total of 15 tunnels. The total distance of the tunnels was 6,213 feet, which was believed to be impossible to finish. Originally, several kilograms of black powder were used each day, but the progress was slow. Next, the team utilized dynamite, sometimes known as nitroglycerine, a recently invented but extremely hazardous product. Nitroglycerine was unstable, easily creating huge explosions: six Chinese workers were killed by the nitroglycerine explosion in April 1866. Fortunately, nitroglycerine was no longer used for Transcontinental Railroad construction. However, this ban was not for the safety of workers, but due to the patent restrictions posed by the inventor Alfred Nobel. The Central Pacific did not prioritize the safety of workers but rather solely hurried for faster progress.

Wishing to accelerate the construction’s completion, Charles Crocker hired Cornish workers from Nevada silver mines to dig the tunnels. Cornish miners, coming from Southwest England, were recognized as the best miners worldwide. Crocker then led a competition between the Cornish miners and the Chinese, hoping to speed up the work. He commanded the Cornish and the Chinese to chip from the middle of a rock in different directions. As Crocker described the results of this competition: “We measured the work every Sunday morning; and the Chinamen without fail always out measured the Cornish miners; that is to say, they would cut more rock in a week than the Cornish miners did, and there it was hard work [sic], steady pounding on the rock, bone-labor.” Crocker praised the hard work and satisfying efficiency of the Chinese. However, he still offered Cornish workers higher wages, indicating that skin color weighed more than capabilities.

The proven success and efficiency of employing Chinese laborers saved Crocker and the Central Pacific. On the Sierra Nevada, it was no secret that the company needed financial aid. The economic hardship forced Crocker to be more dependent on Chinese laborers. This urgent need for Chinese labor was later proven detrimental, leading to the strike. In February of 1867, Crocker asserted further labor needs to Collis Huntington. It was the time of the year when the Chinese were far from being subservient because of the Chinese New Year, their most important celebration. As Crocker felt relieved when the festival was over and expected them “to be coming along from [it] pretty fast,” he realized the further need for obedience. In contrast, the Chinese continued their disobedience rather than building the railroad efficiently, deviating from Crocker’s ideal plan.

However, the Central Pacific still regarded the expansion of the labor force more than anything. The human resources agents mingled through every major mine to look for potential Chinese workers, with the ultimate goal of finding twenty thousand “prospective unbleached American citizens” to join.

Such an aspiration was far from the truth. In April, the weather in California would not inspire optimism: heavy snow and storms largely impeded the construction process. Amid challenges, Crocker admitted the only hope remained to be “the prospect [that] seems favorable for getting a large force of chinamen.”

On May 16th, with the investors and capitalists present at the work site, Crocker commended the Chinese for their impressive work. He recorded the capitalists’ satisfaction in general: “They all express their astonishment at the magnitude of the work already finished and at the comparatively low cost. The cheapness is due in a great measure to the low price of Chinese labor. It is opening the eyes of our businessmen to see the readiness with which this class of cheap labor adapts itself to the construction of railroads.” With their appraised productivity, the Chinese workers became aware of their unique importance as a united labor force.

Despite Crocker’s continuous effort to hire more workers for the construction, the number “came in very slow.” The Chinese were opposed to joining the Central Pacific and were therefore looking for other working opportunities. As Crocker speculated, “The truth is the Chinese are now extensively employed in quartz mines & a thousand other employment new to them. Our use of them has led hundreds of others to employ them—so that now when we want to gather them up for the spring & summer work, a large portion are permanently employed at work they like better.” In essence, the obedient and productive qualities that the Central Pacific desired for the Chinese workers enabled them to chase their own dreams in other places, which the company could not help them attain.

Not only were fewer workers coming in, but even more were leaving for other states in 1867. The Daily Alta California reported that thousands of Chinese moved to Nevada, Montana, and Idaho for jobs with higher wages in 1867. The principals and leaders believed a wage raise of 13 percent would attract more workers. Crocker wrote to Huntington the motive of this voluntary move: “The question whether we can get all the chinamen we need is very important, & we have concluded to raise their wages from $31 to $35 per month & see if that will not bring them.” The wage hike did not match the expected success, however, as additional laborers continued to come in slowly.

Organizing the 1867 Strike

A tremendous tunnel explosion triggered the strike. On Wednesday, June 19, the disastrous “thunder” shocked the Chinese workers. The explosion instantaneously killed “a white man” and “five Chinamen,” who were “horribly mangled” and “blown up.” The shocking news reverberated in the work sites across miles, with the Chinese consequently deciding to halt the operations by throwing in their tools. Five days later, when the construction speed was supposed to accelerate, three thousand Chinese dropped the tools and stopped working in unison. The workforce ranged 30 miles, from Cisco to Truckee. The Meadow Lake Sun commented on the resistance as “the greatest strike ever known in the country.”

A previous strike in 1859 might have inspired the Chinese to resist courageously. More than a decade earlier, fellow Chinese workers in California worked on a railway prior to the Central Pacific next to Sacramento. They held a strike because the contractor refused to pay their wages, thus prompting the rebellion by threatening him with violence. If there was anything profound about the 1859 strike, it must have been that it was continuously told throughout the Chinese community leading to a similar resistance in 1867. The Central Pacific, however, was completely oblivious to this pivotal incident. The corporation was unaware and did not expect methodical and organized resistance.

The workers decided on this specific date according to the directions of Chinese cosmology. Their tradition lasting over thousands of years guided them to begin the strike days after the summer solstice, which was the longest day of the year. In Chinese cosmology, the moon represents female energy and the sun represents male energy. Thus, the summer solstice symbolized when male energy reached its zenith. In the Year of the Rabbit based on the Chinese zodiac, Saturday and Sunday were days to finally plan and gather for the final strike. Correspondingly, this time marked the Chinese’ strongest bargaining power because of the urgent need for the Central Pacific to finish the construction. If it did not finish the Sierra project soon enough, the company would have likely faced bankruptcy.

The request of the Chinese was to have equal wages with white workers. They bargained for 40 dollars per month with a reduced work shift from eleven hours to ten a day. In addition to the aforementioned request, the Sacramento Daily Union, an authoritative local newspaper, reported the workers fought against “the right of the overseers of the company to either whip them or restrain them from leaving the road when they desire to seek other employment.” The source essentially provided credible evidence that the Chinese were utilizing the company’s current weak standing and its unjust treatment of the Chinese as factors contributing to the protest.

The Central Pacific managers were agitated. As no one expected a sudden resistance, they failed to react to the workers in time. James Strobridge, the head of the construction workforce, reported to Charles Crocker the disturbing news in a letter, writing that the “chinamen have all struck for $40 & time to be reduced from 11 to 10 hours a day.”

On the other hand, the Daily Alta California specified that the Chinese wanted even less work time of eight hours per day. Crocker, upon receiving the news, immediately headed to the frontline to confront these “troublemakers.” Meanwhile, Treasurer Mark Hopkins acknowledged the difficulty in resolving the situation. In his letter to vice-president Collis Huntington, he explained the conflict in economic concepts: “When any commodity is in demand beyond the natural supply, even Chinese labor, the price will tend to increase.” Referring to the Chinese workers, he admitted that the company was in a weaker position in regard to the workers. However, he was still confident that the workers “will be controlled by us.” These untested words eventually turned out to be correct.

The strike created a stalemate between the company and the workers. The workers gathered supplies and refused to work peacefully. On June 27, 1867, Crocker wrote to Huntington to express his view that the Central Pacific could not give in: “[The company] cannot submit to it — for they would soon strike again, & we would always be in their power.” To resolve the strike’s potential negative impacts, he attempted to hire new workers. The company tried to hire five thousand freedmen to replace the Chinese, but it never became a reality. He eventually had to recognize the severity of the strike: “This strike of the chinamen is the hardest blow we have had here.” Crocker did not consider overcoming Mount Sierra under harsh storms and slow progress the “hardest,” but the strike demonstrated the Chinese were able to impact the fate of the Central Pacific significantly.

In July, the company refused to satisfy the Chinese workers’ needs despite zero progress. Crocker met personally with some leaders of the strike, possibly including Hung Wah, a leader of the Chinese workforce. He once again stressed that the company would not be able to raise wages above $35 per month. However, the Chinese were unprecedentedly united: workers, contractors, headsmen, and leaders were never divided, and all aimed at the company. The unknown strike leaders demanded, “Eight hours a day good for white man; all the same good for Chinaman.”

All they sought and fought for was equality rather than privileges. However, their protest for equality and justice was never recognized, as Charles responded: “John Chinaman no make laws for me; I make laws for Chinaman. You sell for $35 a month, me buy you sell for $40 and eight hours a day, me no buy.” One might observe the confusing syntax in Crocker’s former quote. Interestingly, Charles’ articulation of his bargain with the Chinese included grammar accommodations aligned to Chinese. Since almost all Chinese were far from being proficient in English, Crocker used Chinese syntax for them to better understand his stance to convince them.

Nowadays, the perception of the strike is largely derived from Crocker’s perspective. Based on all his letters and documentation, it is plausible to conclude that the Chinese represented obedience and discipline as they worked in accordance with the company’s expectations. However, his documents might not fully recognize the side of these workers.

One reason for Crocker’s portrayal of the Chinese workers was to attribute to himself the control and good management of these workers. This was crucial because Crocker represented the perspective of the Central Pacific Railway and therefore, his view described the company’s operating method as working positively. However, other evidence provided a contrasting view.

Comte Ludovic de Beauvoir, a young French visitor to tour California depicted Chinese as nothing like quiet. He first acknowledged the indispensability of the Chinese and their fascinating productivity. However, he then claimed that they adopted “the worst part of Anglo-Saxon civilization.” In other words, he believed this “worst part” was holding a strike. Amid the company’s rejection to compromise with the Chinese, he reported that the Chinese “left their pickaxes buried in the sand and walk around with arms crossed with a truly occidental insolence.” His depiction was completely opposite to Crocker’s description and the general stereotype of the “inoffensive” nature of the Chinese, but rather feeling entitled and arrogant.

The July strike did not last long as it ended in a week. The Chinese labor agents stopped supplying the workers with food and necessities. E. B. Crocker described that this state was severe enough that “they really began to suffer.” The company did not wish to demonstrate any uncertainty and weakness, and therefore, did not approach the Chinese during the strike initially. But later, Charles Crocker, fearing that the workers would realize the company’s pessimistic condition, “went up, & they gathered around him & he told them that he would not be dictated to, that he made the rules for them & not they for him,” according to E.B. Crocker.

Charles Crocker promised that if the workers returned to work instantly, their wages would not be penalized in June. However, if they persisted in resisting, their wages for June would be docked. The Chinese argued back for a small wage increase, but Charles Crocker refused to give in because he believed he could prevent further strikes if the company remained firm. Most Chinese then returned to work with some still resisting and pledged to “whip those who went to work & burn their camps.”

The division among the workers was thus potentially the fundamental reason for the strike’s eventual failure. Charles Crocker promised the safety of the returning workers by “shoot[ing] down any man that attempted to do the laborers any injury.” He armed the camps with guards and a sheriff to prevent violence. This finally marked the end of the strike, which, according to E.B. Crocker, had overwhelmed Charles.

Reactions to the Strike

The strike’s failure seemed to extinguish the Chinese miners’ American Dream. Regardless, the common perception that the Chinese completely lost was inaccurate. Their collective efforts proved to the company that they were not easy people. The company leaders learned that the workers should be treated with respect because the latter “had gotten smart.”

What was scarcely mentioned was that the company secretly improved their pay to the Chinese workers in future months. At least for the skilled workers, wages were increased to $35 per month. Compared to their wages three years ago at $26 a month, this raise was approximately 50 percent higher. This development was key because it contradicted the misconception that the Chinese gained no benefits from the strike. In addition, their collective efforts with discipline and determination amazed the company’s leadership. Charles Crocker commended and showed respect in his words to the Chinese for their manner in the strike more than once, as it was unlike typical ones, where people would fall into “murder and drunkenness and disorder.” He described the Chinese Railway Strike as “just like Sunday along the work.” The fact that the strike used peace and negotiation as primary tools earned the Chinese a positive reputation within the company.

The peaceful strike was significant because it pioneered and inspired future labor protests on the railway. The Chinese workers later initiated similar minor work stoppages regularly. In August 1869, the workers next to Stockton, California refused to work because the company stopped paying wages. In the following decade, more than a thousand workers in Santa Cruz Mountains used the “strike” as a weapon to fight against being mistreated. In 1875, three thousand Chinese in Tehachapi Pass struck together peacefully. These strikes scarcely helped the Chinese to gain material demands. Rather, the Chinese succeeded in demonstrating justice and courage as a part of the Chinese spirit and earned them respect, which could also be viewed as a victory.

The company soon recovered from the damages of the strike. E.B. Crocker, in a letter to Huntington on July 6, 1867, commended the extra effort the Chinese put into furthering the railroad: “The Chinese are working harder than ever since the strike.” In a sense, the Chinese were “atoning” for their presumed “mistake” of holding a strike by constructing rapidly.

Additionally, more Chinese workers arrived at the company. As Crocker reported, “There is a rush of chinamen on the work. Most of the fresh arrivals from China go straight up to work. It is all life & animation [sic] on the line.” Crocker was confident that with the positive achievements and number of Chinese workers, the company would recover economically soon. The new workers would decrease the bargaining power of old workers as supply increased. The company could thus prevent future strikes from occurring. This increase in Chinese labor, nonetheless, foreshadowed further xenophobic sentiments toward the Chinese, as they filled in working opportunities for the whites.

The Central Pacific championed bringing more Chinese workers to the company. On one hand, the Chinese labor contractors encouraged “a large immigration to come over & work on the road next year.” Their words provided E.B. Crocker the optimism that the company would “induce thousands to come over.” The company also coordinated steamship companies to offer appealing arrangements to bring the Chinese over. Crocker announced that he “wanted 100,000 chinamen here, so as to bring the price of labor down.” Huntington concurred with Crocker’s plan, and furthered it in his letter: “I like the idea of your getting over more Chinamen; it would be all the better for us and the state if then should a half million come over in 1868.”

The population of California in 1860 was below 400,000. Considering that Huntington wanted to bring in the number of Chinese exceeding the Californian population, the company undoubtedly brought as many Chinese as they possibly could. Of course, the final recruitment number was not close, but it was still considerable at around 20,000 Chinese workers from 1865 to 1869.

After the strike, Chinese workers continued building the Transcontinental Railroad as before until its completion. The Central Pacific and the Union Pacific connected at Promontory Summit, Utah, in May 1868 as the Chinese workers laid the last two rails. The tremendous frontier project featured the first transcontinental railroad traversing a total of 1,776 miles. The famous photo “Last Spike” captured excitement upon the completion of the construction. In A. J. Russell’s photograph “East and West Shaking Hands,” the chief engineers for the Union Pacific and Central Pacific shook hands surrounded by other engineers cheering with bottles of beer and laughter. Behind the contributors were two locomotives facing each other representing both railway companies. Some railway workers from Eastern Europe were visible in the back wearing dirty garments. This iconic photo, nevertheless, did not include the Chinese, who comprised 90 percent of the total workforce.

The Transcontinental Railroad’s overall success soon drew national attention to the investors. As it shortened the travel time to cross the nation from months to days, the railroads encouraged more people to explore and travel to the West Coast. Western cities underwent an explosion of population growth, industrialization, and agricultural production due to the railway connecting new frontiers.

With Western development, the concept of the Big Four arose, representing four ambitious railroad tycoons that funded the Central Pacific: Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker. Because of their relatively successful management of the company and its workers, they were able to establish a railroad industry in the West. After the completion of the railroad, the Big Four generated huge profits from levying commerce fees on the Transcontinental Railroad. To take the most mentioned businessman in this essay as an instance, Charles Crocker built a mansion in San Francisco after becoming the president of the Southern Pacific Railroad of California in 1871. When he passed away in 1888, his assets were approximately $40 million, equivalent to the purchasing power of more than $1 billion today. Leland Stanford, on the other hand, founded Stanford University in 1885. Their stories became the best exemplars of attaining the American Dream.

Beyond Promontory, the Chinese workers continued to transform the American continent with their strong work ethic. Many newspapers offered eulogies to the Chinese in the article “The Chinaman as a Railroad Builder,” as it spread across the nation, reprinted in famous publications such as Washington D.C.’s National Intelligencer and New York’s Scientific American. The article stated that the railroad could never leave California without the Chinese. Not only did it commend the endurance, discipline, and excellent mechanical skills of the Chinese, but also compared the Chinese to whites: “[The Chinese] are more clever in aligning roads that many white men who have been educated to the business.” Similarly, the Daily Alta California compared the work of the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific and reached the following conclusions: “[The Chinese] do a better, neater, and cleaner job, and do it faster and cheaper than the white laborers from the East.” With such praise, the positive perception of the Chinese eventually led to a brief period of opportunities.

Such praises presumably could open a gate for the future of Chinese workers. They seized the opportunity by joining other railroad construction projects. Their obedient but not docile reputation largely based on the strike helped them to be recruited in Eugene, Salem, and Portland within Oregon in 1868. Some others joined the railroad connecting Truckee and Virginia City. In the early 1870s, they had participated and contributed significantly to major railroad construction sites across the country. No matter where they traveled, they always left positive impressions of having profound experiences and excellent attitudes.

The Aftermath of the Construction

The Chinese laborers might have gotten what they bargained for after the strike, but a massive economic recession ruined their future. Their reputation as great workers established in the Central Pacific soon faded away as the economic recession in the 1870s kicked in. The Long Depression beginning in 1873 moved the United States to adopt a gold standard. As Jay Cooke & Company, a prestigious bank, failed, the Northern Pacific Railway lost its funding source with its bond prices plummeting.

The Panic of 1873 eventually bankrupted 121 railroads, wiped out more than $15 billion in today’s price, and destroyed more than 18,000 businesses. Moreover, it fundamentally changed the fate of railroad workers. Unemployment surged to 14 percent nationwide, with New York’s rate getting as high as 25 percent. Outraged white workers targeted the Chinese: To them, the hardworking Chinese were the worst competitors. Meanwhile, the new white migrants from the East Coast viewed the Chinese as a threatening force that should not be entitled to live with them in the New World. The Gilded Age, as most white workers realized, was not their time to achieve the American Dream.

White supremacist groups violently conducted “the great purge” of the Chinese. In 1871, a Chinese quarter in Los Angeles was attacked by five mobs, who burned down the building, robbed, and shot eighteen Chinese. The surviving victims were forced to head to Southern California since Los Angeles was no longer a welcoming place. Up to this point, this tragedy was the largest lynching event in American history. Twenty-five persecutors were charged with murder, but none of them were convicted or ever received the slightest punishment.

Five years later, similar massacres occurred in Truckee, as hundreds of whites attempted to exile the Chinese. Several white men from a secret group called the Caucasian League poured kerosene into two cabins of Chinese and set them on fire. As the Chinese escaped from their home, the white men killed one and injured the others. Although these white men were tried, none were convicted; all got away scot-free. One local newspaper regarded this incident as “one of the most cold-blooded and unprovoked murders ever recorded.” In the next decade, this “Truckee method” of forcing Chinese out of the town largely prevailed as the 1900 census indicated that only two Chinese survived in this region. The anti-Chinese sentiment prevailed nationwide, emphasizing America’s xenophobia during economic recessions.

The government justified anti-Chinese discrimination in the Exclusion Act of 1882. But before this infamous law, prior restrictive laws against the Chinese existed, eventually leading to the Exclusion Act itself. In 1875, one of the first immigration restriction acts, the Page Act, was passed by Congress. The Page Act banned women from “China, Japan or any Oriental country” for prostitution purposes. In reality, it was used to prevent all Asian women from entering the United States. The Act was consequential as it reflected a shift in the United States’ immigration policy, from relatively open to more exclusionary measures. Seven years later in 1882, Congress passed the infamous law, the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned the immigration of Chinese for 10 years and eventually extended to 1904.

President Chester Alan Arthur argued against this discriminatory act using their contribution to the railroad’s construction as he considered the Chinese “were largely instrumental in constructing the railways which connect the Atlantic with the Pacific.” However, it was their outstanding capabilities as construction workers that attracted envy and hatred because they took away white workers’ jobs. While the Chinese workers enabled upper-class businessmen to realize their American Dream, they threatened that of the white working class. In the end, the Chinese workers’ American Dream conflicted with most whites’ American Dream. Consequently, the well-supported Exclusion Act had a profound impact on the Chinese communities and lasted for nearly five decades. During the “era of woe,” Chinese workers were in a dilemma: to return to China with nothing in their pocket or to stay and suffer separation from their families and severe discrimination. Either way, they were unable to achieve their American Dreams.

Conclusion

For a long period, people forgot the Railroad Chinese as time passed, eventually fading into the crowds. On May 10, 1919, three Chinese workers were invited to the fiftieth anniversary of the Golden Spike ceremony. All over 90 years old, Ging Cui, Wong Fook, and Lee Shao now lived in Susanville, Nevada, and retired after over fifty years of constructing railroads. They were dressed in “romanticized” work clothes with conical bamboo hats and trench coats. Beneath the solemn outfits, however, their “shy” and “weary” visages were shown in several blurry photos. Since the ceremony, they were never identified again, not even where they were buried.

It was not until the past decade that this mistreated group was finally recognized and honored. Stanford University initiated the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project in 2012, intended to recover the history of early Chinese migrants. It is worth mentioning that Leland Stanford, the founder of Stanford, despite significantly benefitting from the Chinese workers, did not pay much attention to the Chinese, instead, calling the Chinese “an inferior race.” Stanford professor Gordon Chang noted that “Leland Stanford became one of the world’s richest men by using Chinese labor.” Therefore, Stanford University’s project could be viewed as a redemption, by offering the Chinese deserved recognition. The project incorporated a variety of oral histories and interviews with workers’ descendants, which extensively delved into the past and current perspectives of the Chinese. Moreover, it provided a special section of resources for teachers, enabling this history to be disseminated in the classroom.

The celebration of the Railroad Chinese ultimately culminated at the 150th anniversary of the Golden Spike ceremony. On May 10th, 2019, in Promontory, Utah, the crowds gathered to celebrate the groundbreaking achievement of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Unlike previous celebrations, the Chinese workers’ descendants were invited, along with Irish immigrants, Native Americans, African Americans, Civil War veterans, and Mormons. Along with the Chinese, many of these groups suffered from discrimination during the construction. In the opening remarks, author and historian of the Chinese Historical Society of America Connie Young Yu, whose great-grandfather assisted in building the railroad, honored the sacrifice and courage of the laborers and “felt such elation.” Her speech represented a multitude of Chinese through their family lineage’s sincere longing to bring justice and truth back to this history.

It is reasonable to conclude that white employees and Central Pacific tycoons prevented the Chinese railroad workers from achieving their American Dream. Nevertheless, the Chinese workers demonstrated enough audacity, with only a little luck, to work towards their dream of “instant wealth.” However, their descendants and scholars were seeking their American Dream as more attention to this hidden history appeared. The workers are no longer nameless constructors but recognized builders of their unique history. While they still have not received the full respect and recognition they deserve, their stories articulate the paramount importance and exigence of unearthing hidden histories. This will enable future generations to learn from mistakes and empower marginalized groups. Only if we remember what happened can we avoid repeating history from occurring again.

Leave a comment