In the 1890s, the Gilded Age reached its climax as the Depression of 1893 destroyed the nation’s economy. For one moment, wealthy and middle-class businessmen, farmers, immigrants, and impoverished Black sharecroppers united together to find a way out. Of course, whenever the majority of society, the white people, witnessed unsatisfactory scenarios, they tended to blame them on the weakest group, Black people; because of this, lynchings reached an all-time high. The dilemma of African Americans was far more than brutal treatment. As most of them resided in the deep South, their incomes dropped to almost nothing as cotton and tobacco prices dropped. They still starved as few of them grew any stable crops, to the point that their situation resembled decades ago when slavery still existed.

In the hopeless state, there had to be a Black leader who could stand up to fight for respect disregarding race, no matter by what means. It was believed to be impossible to reach complete political equality for the race, so the Blacks needed a compromise that could satisfy both whites and Blacks. Someone had to exist to lessen the “white reign of terror” in the South.

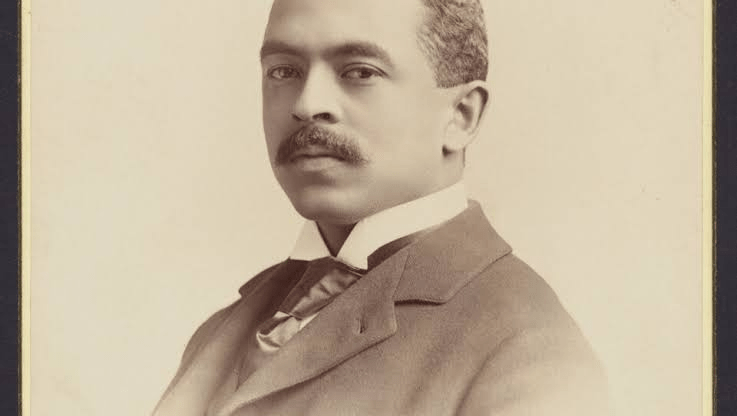

Booker T. Washington, who emerged as a promoter of Black education, was believed to meet the qualifications. In 1881, Washington was recommended to become the first leader of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, later more famously known as the Tuskegee Institute. This marked the first Black school to prepare students with necessary working skills for them to survive in the oppressive society. He not only wanted to “better himself,” but also to better his fellow man. The emergence of Washington marked the early attempt of the Civil Rights Movement, which failed to reach its purpose of discarding discrimination and adopting justice and equality among ethnicities. Washington was criticized for his approaches, as he did not seek direct methods to fight for his fellow people.

The most known speech produced by Washington, the Atlanta Exposition Address, was a ten-minute speech at the Cotton States Exposition in Atlanta on a hot September day in 1895. His audience was not limited to merely inspiring his fellow African Americans to accept segregation as part of the sacrifice to receive education and economic stability. He also intended to impress the whites, mainly the Northerners on the progress of the New South regarding industrial production and ease of racial tension, and encouraged them to invest in the South so that African Americans could also benefit from the economic growth that was brought along with the Northern investment.

Proponents of Washington’s ideas were mainly the middle class, exemplified by Southern Black teachers. “The Negro will have to work out his own salvation. Religion, education, and money will make any race great,” said a Black school principal from Virginia. Others believed that “when the more intelligent classes of the race unite their effort to educate the ignorant classes by example rather than by precept,” many problems faced by the Blacks would be solved. The opponents of Washington were comprised of Black “intellectuals”, as they believed Washington did not appeal to political rights. The emphasis on industrial education made Black people worth more as merchandise than ameliorating the public opinion to view them more equally. One of the most renowned rejections was from W.E.B. Du Bois, who emerged as an unknown figure but rose to become an equivalently distinguished leader of Black rights.

Washington’s approach attracted a multitude of opponents, the most quintessential being W.E.B. Du Bois. His famous critique of Washington was chapter III of The Souls of Black Folk (1903), a collection of non-fiction essays. The work recorded his reflections on the Black freedom struggles in 20th-century post-slavery America. Chapter III, Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others, examined the career and efforts of Washington, with mainly constructive criticism.

Du Bois could not accept that Washington “practically accept[ed] the alleged inferiority of the Negro races.” He emphasized that the Black race could not be saved by “adjustment and submission” only but by “manly self-respect:” “The history of nearly all other races and peoples the doctrine preached at such crises has been that manly self-respect is worth more than lands and houses, and that a people who voluntarily surrender such respect, or cease striving for it, are not worth civilizing.” He listed three things that Washington called the Black people to but could not give up: political power, insistence on civil rights, and higher education of Negro youth. These resulted in “the disfranchisement of the Negro, the legal creation of a distinct status of civil inferiority for the Negro, and the steady withdrawal of aid from institutions for the higher training of the Negro.” He claimed that the race needed more teachers in higher education as opposed to industrial labor workers and advocated for suffrage and civil equality. Washington’s plan was built on the sacrifice of “industrial slavery and civic death” of Southern Black people.

While the debate between Washington and Du Bois was analyzed to a great extent, a less-known newspaper editor and real estate businessman in Boston emerged and also opposed the accommodationist ideals of Booker Washington, William Monroe Trotter. In 1901, he founded the Boston Guardian, a newspaper to express his own take on civil rights as his rhetorical strategy. Born and raised in Hyde Park in Boston, he graduated from Harvard University, having early success as a real estate developer. Interestingly, the Guardian was published in the same building as the former headquarters of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, formed by William Lloyd Garrison. The two magazines seemed to have similar intent to liberate the Blacks, despite through different strategies.

How did Black leaders in the same era diverge in their ideas in completely opposite directions? A part of the reason came from Monroe’s background. His father taught him that he was an individual who was capable and responsible for competing with the best white people. He was brought up in racial radicalism, and his family refused to connect moderates and conservatives. Trotter’s early actions proved his activism: he resigned from working in the Boston Post Office because of discrimination against Black people; he also aligned himself with Democrats as he believed that the Republican Party had abandoned Black people. Indeed, born out of an all-white community of Hyde Park surrounded by intellectuals in Massachusetts, Trotter wanted to blend in with the white community and stand out from there to lead his fellow brothers.

Graduating from Harvard with a Phi Beta Kappa honors, Trotter remained uncertain about his future, or to be more exact, the future of his race. He believed that his temporary success could not help his race to achieve equal rights. As he attempted to seek means to spread his ideas, George Washington Forbes joined him to create the Guardian. The main purpose of this magazine was to fight against the accommodationist Washington. It thus became the main vehicle of agitation.

William Trotter’s rhetorical acts were multifaceted as they combined public speeches, written editorials in the Boston Guardian, and direct protests. His audience and objectives were to inform and pressure the African American community and white elites to galvanize support for Black rights and make political changes. He was known for extending beyond traditional rational arguments and including emotional appeals and nonverbal forms of communication by initiating a protest in the Boston Riot, which was pioneering to social movements. Although William Trotter’s bellicose rhetorical strategy in the Guardian did not succeed in persuading most people to adopt a radical approach to Black rights, his activism and his debate with Washington inspired other Black leaders such as Du Bois and made millions of other Americans aware of Black people’s situation, which contributed to new ideology and ameliorations to rights of his fellow people.

Although much scarcer reviews and research were conducted on Trotter compared to Washington and Du Bois, Aaron Pride, in his theses and dissertations “Black leadership and religious ideology in the nadir, 1901-1916: reconsidering the agitation/accommodation divide in the age of Booker T. Washington,” explored the conflict between Washington and Trotter through the unique lens of religious dimensions. Their conflicting views of Christianity in both Black and white society largely altered the form of agitation in the early Civil Rights Movement. Specifically, Trotter’s voices were considered pioneering to reject submission in the Black church.

Trotter described his four purposes to begin his agitation: firstly, the dissemination of South values aggravated the race conditions while Washington failed to fight back; secondly, Trotter encountered personal setbacks being rejected from the ministry because of segregation; thirdly, Trotter adopted beliefs from his father to physically seek tangible ameliorations for African Americans; lastly and most importantly, Trotter’s loyal dedication to Christianity and his conscience pushed him against segregation using activism.

Indeed, the Guardian carried his religious belief toward justice. The Guardian contained the motto “For Every Right With All Thy Might.” Pride argued that the motto presented Trotter’s personality and roots in Christian values for agitating for the political rights of Black people. As he wrote in the newspaper explaining his interpretation of the phrase “every right,” he wanted to ask Washington:

In view of the fact that you are understood to be unwilling to insist upon the Negro

having his every right (both civil and political), would it not be a calamity at this juncture

to make you our leader?

It is clear that Trotter considers the term “every right” to encompass all the privileges associated with political citizenship and civil society, while “for every right” emphasizes his

dedication to fighting for unrestricted political and civil rights for African Americans.

The second half of the Guardian’s motto is very similar to a Bible verse. As a devout Christian, Trotter was familiar with the Bible, where he considered Bible knowledge a must in life. He documented, “I also read God’s word more than I used to. We must know it to be useful.” “With all thy might,” according to Pride, was a phrase used from the fifth verse of the sixth chapter of Deuteronomy: “And thou shalt love the lord thy God with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy might.” “For every right with all thy might” demonstrated the spirit of God’s revealed militancy, which became the source of inspiration for Trotter’s activism.

“The Gaurdian is an up to date journal,” commented by a veteran Black editor W. Calvin Chase in the Washington Bee. The New York Age, the recognized most-renowned Black newspaper at the time, documented that “Editor Trotter is a man.” Similarly, L. M. Hershaw, in his writings from Charities, called Trotter’s work “the foremost race journal in advocating equal and identical civil and political rights for Negroes.” On the other hand, the commencement of the Boston Guardian encountered severe doubts. Another Black journal, the Indianapolis Freeman, claimed the Boston Guardian might “carry its cases too fast and too far.” Indeed, the emergence of the novel Black newspaper attracted so much attention that even those who disagreed with its opinions and arguments accepted its journalistic presence. To this aspect, it seemed to suit Trotter’s description of it as “a clean, manly, and newsy race paper.”

The audience of the Guardian were national advocates of the early Civil Rights Movement. As a newspaper published every Saturday, it consisted of eight pages that included both local Boston and national news of Black people. The Guardian looked for sources across the whole nation, including both Black journals and white papers. To this extent, this proved that Trotter was determined to use the Guardian not merely among his fellow Blacks, but also to attract those enthusiasts from different races. Trotter actively searched for negative news about Washington far away from Boston, but also other major cities such as Washington D.C., New York, and Chicago. This was his strategy to pull subscriptions and readers out of New England to spread his influence. Lastly, the issue usually included some other topics such as fashion and sports information, fiction, and Church news to increase the breadth of coverage. The price of five cents a copy and 1.5 dollars for a whole year’s subscription ensured that the audience could afford this means of persuasion.

Different from Washington, Trotter adopted a “bellicose” rhetoric strategy. Trotter presented the rhetorical situation as a crisis and wanted to desperately change it, despite sometimes being arrogant, while Washington viewed the situation more positive and optimistic. A contrast between Washington’s words and Trotter’s arguments juxtaposed between hope and brutality. Washington believed that “Merit, no matter under what skin found, is in the long run, recognized and rewarded.” Trotter had less optimism and perceived the future of the Black situations with more negative concerns: “a spirit of ruthless and rapacious domination of his interests by them from the foundation of the republic.” Whatever Washington claimed, Trotter seemed to always be able to find a rebuttal. For instance, Washington sought for real achievement in “constructive work” rather than focusing on denouncing what was wrong. He famously declared in his speech that “there is no hope for any man or woman… who is continually whining and crying about his conditions.” Trotter, however, asked for the “spirit of protest of independence, of revolt” and criticized those “playing the part of the timid, or the cowardly.” In this context, Trotter almost directly attacked Washington by calling him “timid” and “cowardly.” He later argued that “The policy of compromise has failed… The policy of resistance and aggression deserves a trial.” His urgent tone to call for action created public discourse over the proper strategies of the Civil Rights Movement.

A cause exacerbating the conflict was the worsening of Black rights in the center of Boston. Ray Stannard Baker wrote in 1908, “A few years ago, no hotel or restaurant in Boston refused Negro guests; now several hotels, restaurants, and especially confectionary stores, will not serve Negroes, even the best of them.” To Trotter’s dismay, Washington did not stand out and condemn such a situations, which made Trotter believe Washington was also a catalyst for the worsening condition of Boston’s increasing racism. Interestingly, he used the rhetoric of imitating language from a historical event, the Dred Scott case. The Guardian stated “the northern Negro has no rights which Booker Washington is bound to respect. He must be stopped.”

The second main difference in their strategies lies in their distinct views toward Black education. Trotter rejected Washington’s ideas of industrial education. He objected industrialism because Washington’s relinquishment of Black elitism “is the relegating of a race to serfdom.” To some extent, Washington admitted the natural intellectual inferiority of the Blacks which enraged Trotter: The “reason why industrial education is more popular with the general white public than advanced or classical education.” He used himself as evidence of the necessity for Black people to attend and thrive in colleges and above, finally proving that their mental capacity was nothing less than the other race. To this extent, Trotter emphasized more on the long-term impacts of education, such as involvement in politics and voting rights, while Washington viewed these more like luxuries.

Trotter frequently used the master trope of metaphors to highlight the importance of Black suffrage. He called the ballot “a sacred right” as a necessary condition “without which nothing satisfies us.” He viewed the Black ballots as a chained elephant because the Republican party had left Blacks behind, but they still got the majority of Black votes. This absurd situation showed that most Black beliefs were outdated and far away from achieving progress. Instead, he argued that voting should be “the new war cry of Negro freedom.” The metaphors here bring the known out of the unknown by presenting the danger of insufficient Black suffrage.

Lastly, the attack from the Guardian usually ended up personally offending Washington. The newspaper referred to Washington as “Pope Washington, the Black Boss, the Benedict Arnold of the Negro race, the Exploiter of all Exploiters, the Great Traitor, the Great Divider, the miserable toady, the Imperial Caesar, the heartless and snobbish purveyor of Pharisaical moral clap-trap.” After Washington presented a speech in Boston, the Guardian immediately characterized his stature:

His features were harsh in the extreme. His vast leonine jaws into which vast mastiff-like rows of teeth were set clinched together like a vice. His forehead shot up to a great cone; his chin was massive and square; his eyes were dull and absolutely characterless, and with a glance that would leave you uneasy and restless during the night if you had failed to report to the police such a man around before you went to bed.

The characterization of Washington was mainly negative, with a tone of condescending and mocking. Obviously, the editor did not favor Washington’s plans and, therefore, called him “characterless”. His visage also left an impression of being scary, as the editor portrayed a scene about finding the police. In 1903, both Troguartter and Forbes believed that the Guardian did not reach the extent of success that they wished in order to diminish Washington. They therefore went to Louisville to meet the Black leader in front of the national convention of the Afro-American Council and present their radical solutions. Their direct method, however, was immediately turned down by Washington’s friend and supporter, the conference chairman, T. Thomas Fortune. Washington remained moderate in his criticism of his opponents from Boston:

“I am used to attacks, I have no ill feeling against Trotter or Forbes. I think they misunderstand southern conditions, however. If they had been through my experience, I do not think they would express the views that they do.”

This seemingly restrained comment agitated Trotter, and he became determined to embarrass Washington in Boston. His awaited chance finally arrived on July 30th, 1903 in Boston’s A.M.E. Zion Church. Trotter led two followers to yell out fierce questions to Washington, ignoring the objections of the chairman, William H. Lewis. Red peppers were thrown at Washington and the crowd soon called the police. Trotter, his two friends, and his sister Maude were arrested and brought away as Washington finally had the chance to speak. This event was later known as the “Boston Riot.”

Trotter attempted to explain the cause of the riot in the Boston Globe: “The cause of the riot at the colored Methodist church was due to the absurd ruling of the chairman, W.H. Lewis, when he said that anyone who hissed or manifested objection to the speaker of the evening, or who demanded the right to ask him to explain some of his previous statements favoring disfranchisement, and discriminating in Jim Crow cars, would be subject to arrest.” To this extent, this strategy of waging opposition against Washington failed. This is because as he tried to read his nine questions for Washington when everyone else was in chaos, no one could hear him. A supporter of Washington, Dr. Samuel Courtney, shouted “throw Trotter out the window!” Thus, Trotter and his sister were arrested: the brother accused of disrupting peace, and his sister for stabbing a police officer.

The Boston Riot was also a failed attempt because Trotter made the whole nation his enemy. Since 1892, Monroe Trotter has been steadfastly moving forward under the inspiration of God. His career and business slowly succumbed to the demands of sedition. The nation now scorned his name. The Boston riots tarnished his reputation and threatened his freedom. “The cause for which I am contending is for me a sacred one, and therefore I am desirous of having it known that it is a man of good repute who was willing to be arrested for this cause,” Trotter said.

To some extent, Trotter’s rhetorical strategies were similar to those emphasized later in the rise of rhetoric in social movements. As Jenson argued, the early social movement rhetoric, especially starting from the 1960s, deviated from traditional forms of expression of great speeches and public speaking based on rational argument. Instead, they transitioned into more radical and irrational approaches including slogans, marches, protests, and other nonverbal forms of communication. While the trend might emerge late in the Civil Rights Movement, to much extent, Trotter’s rhetoric seemed to echo such changes. He showcased what it means to be an activist by constantly pressuring changes in front of important figures like Washington through radical publications in the Guardian, and extreme protests in the Boston Riot. It is acknowledged that the early Civil Rights Movement might not have moved from the bottom up, as mainly Black leaders were prompting the changes, which was a widely agreed upon criterion for a social movement rhetoric proposed by Waite Bowers and Donovan Ochs in The Rhetoric of Agitation and Control. This proved that the evolution of social movement rhetoric progressed gradually, with some features already established in the early 1900s, but others to be formed later mainly from the post-World War II Civil Rights Movement.

The riot itself had a profound impact on the future Black leader W.E.B. Du Bois. He expressed admiration for Trotter’s “unselfishness, pureness of heart and indomitable energy.” When Trotter was in prison, Du Bois was outrageous: “my indignation overflowed. … to treat as a crime that which was at worst mistaken judgment was an outrage.” These were examples of examining rhetorical acts, a concept proposed by Gaillet, which in this context means taking direct actions against Washington. Gaillet also emphasized the importance of creating a narrative, which was achieved as Trotter depicted himself as an unrelenting advocate for Black rights. It ended up drawing Du Bois to join the militant wing of the movement. As Du Bois later sought collaboration with Trotter in the Niagara Movement, they expanded their rhetorical spaces that challenged existing power structures. They were able to make a stronger presence in the public, no matter through holding protests or publishing materials to galvanize support.

The Boston Riot, as a national dispute, was historically significant because it was the first direct opposition of Black people to their leader. This essence surprised both races across the nation and brought this debate into the eyes of so many others. Thus, the topic of civil rights was once again brought to the frontline of discussion, as the event served as a frontier to future discussions and debates. That said, the debate between Washington and Trotter proved that the form of controversy and public discourse served as a more appealing and attractive hook and exigence to national attention. Neither Washington’s accommodationist approach nor Du Bois and Trotter’s radicalism reached success because their beliefs never got implemented wholly. However, whether whose belief was more appropriate mattered little compared to the consideration process they triggered among millions of others. To this end, the debate itself served as a successful model of rhetoric for social change.

The debate in the Progressive Era inspired similar but more successful debates in the Civil Rights Movement. One can often draw a parallel between Washington and Martin Luther King, in their relatively moderate approaches to improving the lives of African Americans compared to Trotter and Malcolm X. Although King adopted more active strategies of civil disobedience to challenge segregation and discrimination, both King and Washington’s activism centered around nonviolent resistance that earned them the respect of white people. The Progressive debate’s legacy, therefore, should not be limited to a failed attempt of his era but a testament to the enduring struggle for equality, which ultimately set the stage for more radical and comprehensive efforts of leaders like Martin Luther King Jr.

Leave a comment